in the late 19th and early 20th century

God made meat, but man makes lard.

— an anonymous Chicago trader quoted in “The Perilous Game of Cornering the Crop” by Isaac Marcosson. Munsey’s Magazine, Volume 42, No. 1. October (1909).

The Founding Fathers of Meatpacking

By the later half of the nineteenth century in the Mid-western United States, huge meatpacking houses had developed a vast infrastructure in Kansas City, Milwaukee, Cincinnati and Chicago. These houses were the creation of the captains of meatpacking and its associated industries – Philip Armour, John Plankinton, William Proctor & James Gamble, John and Patrick Cudahy, Nathaniel Kellogg (N.K.) Fairbank, Gustavus Swift and others – these men were, in fact, the revolutionary Founding Fathers of the modern U.S. meatpacking industry.

Along with these founders, there was also a second tier of like-minded men primarily distinguishable by lacking the same level of financial backing as the founding fathers. Men like Peter “Uncle Peter” McGeogh of McGeogh, Everingham & Co., The Fowler brothers (later George A. Fowler & Son), James Wright and others who were referred to as minor industrialists. And of course there was also a lower tier of individuals variously characterized as investors, speculators, market manipulators or opportunists.

Lard is A Well Greased Commodity

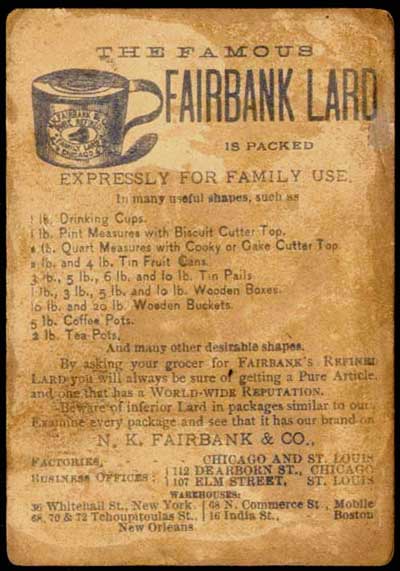

Lard had become a major household commodity for the meatpacking industry. Lard was profitable and consumer demand was expected to grow as new markets were opened and the U.S. population, especially in cities, continued to grow.

Profitability in the manufacture of such a high demand consumer item necessitated strict attention to cost control. In the market arena of lard the N.K. Fairbank Co., its competitors, and also commodity traders, speculators and numerous raw material suppliers were all in a game to catch that greased pig of profitability. Potential rewards called them forward but market slips and days covered in mud were unavoidable.

The packing business is done with a lead pencil, not with a knife. It is a matter of calculation, not butchering.

— Phillip D. Armour quoted in “The Perilous Game of Cornering the Crop” by Isaac Marcosson. Munsey’s Magazine, Volume 42, No. 1. October (1909).

The Board of Trade and the Produce Exchange in Chicago were the center of trade and market speculation for lard in the late eighteenth century. Peter McGeogh, George Fowler and N. K. Fairbank, among others, all with businesses based in Chicago, were very active in the lard market. And because of their few notable successes and headline-grabbing failures in lard speculation, these greased pig chasers would variously attain and then loose claim to the media-endowed title of the “Lord of Lard.”

A Cycle of the Lard Lords

An example of such a slip in the market occurred in June of 1883, when Peter McGeogh, attempting to ease a failure to meet his obligations in a failing lard speculation, accused “wholesale adulteration in $30,000 worth of lard tendered him by James Wright & Co. and Fowler Bros. & Co.”1 A subsequent market panic in lard ensued in Chicago and spread to secondary markets in New York. Ultimately McGeogh lost a substantial sum.

Following McGeogh’s June losses, the newspapers revoked this previously praised speculator’s title of “Lord of Lard.” And only a month later, N.K. Fairbank was crowned with the revolving title as market confidence was restored when Fairbank, with support from Phillip Armour and Fowler Brothers, began buying up lard in great quantities in expectation of a coming bull market.2 And the cycle of Lords of Lard continued.

100% Pure (mostly)

Accusations of adulteration among the Lords of Lard and those who speculated in lard were routine in the late nineteenth century. Lard or “prime steam lard” was the technical term for pure hog fat, but such a pure item almost never reached the end consumer. Regular adulteration of lard, a response to market forces, was carried out at this time by the addition of varying amounts of any combination of the following: 3

- terra-alba – finely pulverized gypsum used as a pigment and filler

- oleomargarine sterine – solids extracted from beef fat

- “olive butter” actually made from cottonseed oil

- tallow – fat from beef or mutton

- various vegetable oils

- water

But this adulteration [of lard] is no new thing. It has been done for years. The trade demands it; competition with other cheap goods has to a great extent made it necessary… In order to furnish an article to suit the price people are willing to pay, alteration is resorted to. The people generally who pay such a price must expect to get an adulterated article.

— ‘one of the oldest and most prominent dealers in provisions at the [Chicago] Produce Exchange’ as quoted in “Adulterations in Lard.” New York Times, June 3, 1883.

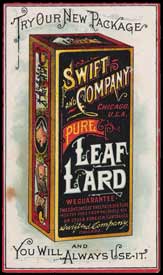

As the quote above suggests, lard adulteration was likely carried out at all levels from the primary branded manufactures like Swift, Armour and Fairbank companies and on to the Wrights, Fowlers and the smallest processors. Yet all routinely denied it, unless one manufacturer or supplier could be accused by another in order to secure a competitive market advantage.

“never enough of them left to be worth exhibiting”

Another great challenge faced by the meatpacking’s Founding Fathers and the Lords of Lard was overcoming consumer mistrust of processed meat products and lard. This mistrust arose from several circumstances.

The impersonal nature of the vast, mechanized meatpacking industry, as contrasted with the presumed quality of the alternative – farm-raised and processed products available locally from a neighbor or merchant – was a common concern.

Also the often-sensationalized exploits of Chicago’s Lords of Lard became increasingly documented in newspapers across the country. For consumers, the accusations of adulteration that passed around between the producers and suppliers gave rise to growing concerns for the quality of the wide variety of food products that reached their family’s tables.

…and as for the other men, who worked in tank rooms full of steam, and in some of which there were open vats near the level of the floor, their peculiar trouble was that they fell into the vats; and when they were fished out, there was never enough of them left to be worth exhibiting, — sometimes they would be overlooked for days, till all but the bones of them had gone out to the world as Durham’s Pure Leaf Lard!

— Upton Sinclair. The Jungle, Ch. 9

Practices by the largest packers, such as Swift and Armour, were more regularly focused on quality and not just costs alone, a luxury afforded them by their greater financial stability. But public opinion fixated on food safety and the newspapers attention focused on the frightening tales that arose primarily from the smaller and more speculative meatpacking companies and facilities.

Promotion Becomes Defense

Man must live, and to live he must eat. He will not brook any tampering with the sources of his food.

— Isaac Marcosson. “The Perilous Game of Cornering the Crop.” Munsey’s Magazine, Volume 42, No. 1. October (1909).

Public uproar about food quality and safety increased as the eighteenth century ended. Advertising and public relations that had created the beautiful and persuasive promotional trade cards shown above and featured in the Art Museum became a more defensive operation.

Sinclair’s 1906 muckraking novel The Jungle exposed conditions in the U.S. meatpacking industry and other investigations made public issues in the production of other food products as well. The awareness and out cry of the U.S. consumers contributed in part to the passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act.

Additional Information:

The growth of the mid-western meatpacking industry throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is a fascinating aspect of the industrial history of the United States. Here are some additional sources of information:

- A Brief History of Fairbank (N. K.) & Co.

- Meatpacking – The Chicago Historical Society

- History of the Board of Trade of the City of Chicago by Charles Henry Taylor. Chicago: R.O. Law (1917).

- an enhanced version of the lead image for this entry is available on the Porkopolis.org Flickr site