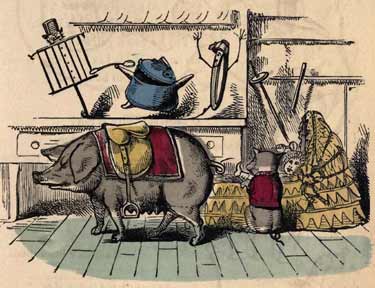

The sow came in with the saddle,

The little pig rock’d the cradle,

The dish jump’d over the table,

To see the pot with the ladle.

The broom behind the butt

Call’d the dish-clout a nasty slut:

Odds-bobs, says the gridiron, can’t you agree?

I’m the head constable, – come along with me.The Nursery Rhymes of England (1842).

Saddled sows and bridled boars

What might it be in the British character or psyche that promotes their regular consideration of putting a saddle on a pig? Thinking about saddled sows and bridled boars seems to be a very old tradition in Great Britain.

Five to six hundred year old misericords in British churches like Manchester and Beverly Minster record the British interest in such a concept. Here are images of the supporters of two different misericords from these two churches that suggest this was a concept firmly on the British peoples minds over half a millennia ago.

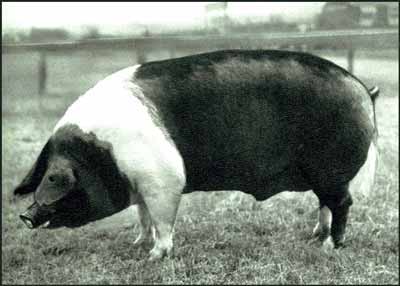

Banded or belted or saddled

The British Saddleback breed of pig was officially recognized in 1967 when the Wessex Saddleback and the Essex Saddleback breeds were amalgamated. The Wessex and Essex breeds date back to 1918 when their herd books were published.

But that is the official record. Long before that time the generic term “saddleback” was in use in Britain to describe several pig varieties, including the New Forest pig.

All the varieties had similar color markings that could collectively be described as a black body with a white unbroken band or belt over the shoulders and down to both front feet. These pigs also usually had lop ears over their heads and may also have had white hind feet, a white tail tip and/or white on the snout.

Banded or belted pigs of this general color pattern are also common in populations around the world, although that does not mean that they are necessarily related. This belted color pattern is more likely a genetically common pattern that re-occurs in various populations of domesticated pigs.

References to the pigs with the terms “banded” or belted” seems to be the dominant descriptive adjective for folks who encounter these pigs, except in Great Britain, where “saddleback” is preferred.

Mother Goose weighs in

The poem mentioning a saddled sow that opens this post is included, in slightly varied versions, in the earliest print versions of Mother Goose (aka: Mother Hubbard) rhymes.  One of the oldest of these is The Nursery Rhymes of England, collected principally from oral tradition, James O. Halliwell, editor, and printed by the Percy Society in London, (1842).

One of the oldest of these is The Nursery Rhymes of England, collected principally from oral tradition, James O. Halliwell, editor, and printed by the Percy Society in London, (1842).

While The complete poetry and prose of William Blake. University of California Press, (2008) also includes the same poem as a favorite of William Blake (1757-1827), listing it as “Mr Blake’s Nursery Rhyme” with references to him reciting it. Could he have heard it as child in the mid-1700s and so become fond of it?

Prior to their being collected in print in the nineteenth century, most of the Mother Goose or Nursery rhymes had already had a long life in the form of oral traditions past through earlier generations. Prior to the mid-eighteenth century print collections, reasonable speculation could easily add one hundred years or more of earlier recitation as “The sow came in with the saddle,” and other rhymes were passed down orally among British families.

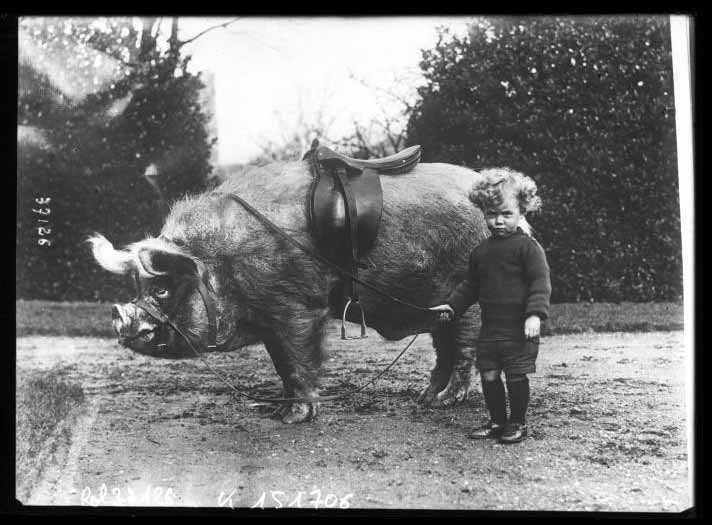

An Edwardian Menagerie

But perhaps the singularly best example of the British penchant for saddling pigs comes from some early twentieth century photographs of the Edwardian Menagerie of Sir Anthony Wingfield (1857-1952) of Ampthill, in Bedfordshire, England. The images below are from Sir Anthony Wingfield’s private zoo or menagerie.

A menagerie of the Edwardian era (ca. 1901-1910), like Sir Anthony Wingfield’s, was a collection of common and exotic animals held in captivity. Menageries were mostly for personal use and curiosity and were owned by individuals – usually an aristocrat or a member of the royal court. They were a means to illustrate power and wealth, as live exotic animals were uncommon, difficult to acquire and expensive to maintain.

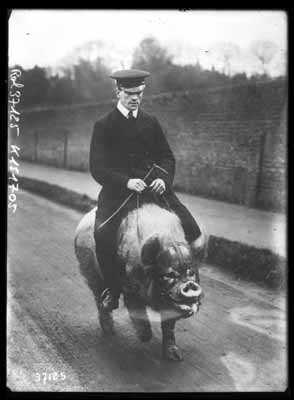

Wingfield’s menagerie featured beasts of burden and saddle. Ladies and gentlemen who were his guests, could ride and be photographed on the most unlikely mounts such as camels, bison, ostriches, llamas, zebras, yaks, exotic asses and a pig.

Here are some images, ca. 1900, of a saddled and bridled boar that was a popular member of Wingfield’s Menagerie. The uniformed man is one of several un-named Menagerie Keepers that Wingfield employed, and the child is unidentified. St. Andrews Church of Ampthill and various scenes of the town of Ampthill make up the background of the images. (Click on the images for an enlarged view.)

Riding to Glory

While the boar pictured above is clearly not of the saddleback variety, there is certainly a saddle on his back. Did Sir Anthony Wingfield hear the poem about the saddled sow recited to him as a child? Perhaps he saw the church misericords, or did other factors induce him to train a boar to the saddle?

I discovered far more diverse and detailed information on saddling up a pig than I could process and include here now, so this post is labled “part 1.” Lets just say the British are not the only folks who have thought about a saddle, a pig and a ride to Glory. I’ll be posting more on saddled pigs in the future.

Additional Information:

- The village of Ampthill in Bedfordshire, England and more information from Towns in Britain

- The British Saddleback Breeders’ Club

- Pressman has more early print versions of nursery rhymes available

Great post. I thought you might be interested in a couple of related references I’ve run across:

The great geologist Charles Lyell, on a visit to Cincinnati in 1842, made the following observation:

“As to the free hogs before mentioned, which roam about the handsome streets, they belong to no one in particular, and any citizen is at liberty to take them up, fatten, and kill them. … It is a favorite amusement of the boys to ride upon the pigs, and we were shown one sagacious old hog, who was in the habit of lying down as soon as a boy came in sight.” (Travels in North America, 1856, vol. 2, p. 61)

Earlier, in 1819, New York City had passed an ordinance against hogs roaming free on city streets. At the trial of one man accused of violating the ordinance, the district attorney produced a number of arguments against allowing free-range pigs, including that “boys got into trouble by riding hogs.” (Hendrik Hartog, “Pigs and Positivism,” Wisconsin Law Review 899 (1985), 905-6)

Though the record is silent on the matter, I would assume that these boys in Cincinnati and New York did not saddle the hogs before mounting.

Thanks, Mark! Your references are new to me and I appreciate you sending them. The subject of saddled pigs &/or riding pigs might turn out to be worth several future posts. I have found a wealth of information beyond what I have included here.