by Hay Machine (e);

Dublin, Ireland. March 2005

To look and walk where the artists walked

the words of those with whom they talked

to kiss the thoughts they might have thought

what am I bid for their palette— from the poem “Sir John and Lady Hazel Lavery” by Hay Machine (e)

In 1868 the Armour Meat Packing Company moved its pork processing operation from Milwaukee, Wisconsin to Chicago to take better advantage of the railroads and stockyards there.

The following year Armour Meat Packing Co. of Chicago added a second plant, taking over a slaughterhouse on Archer Avenue and setting up under the name Armour & Co. And Boston got its first shipment of fresh meat from Chicago by way of a refrigerated rail car developed by William Davis; but the Railroad Industry resisted losing their traffic in live animals bound for eastern markets and charged high transport rates.

Who is to say? When the woodland paths divide, which ones are taken by whom and to what end? William Wordsworth had a theory about the past, I am told. That it was all-important to the living. Because the present is fleeting and the future may not come. By deduction we have only the past to comfort or condemn us.

Edward Jenner Martyn, a fifth generation descendent of the Martyns of Galway in the west of Ireland, entered the firm of Armour & Co. in Chicago as a messenger in 1875 and rose to a senior management position. He prospered and moved up in the world. He acquired a significant residence at 112 Astor Street and there lived a happy, exemplary, fine and fashionable family life with his wife Alice Louise (nee Taggart) and their two beautiful daughters, Dorothea and Hazel.

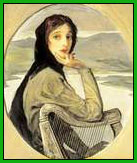

Edward died leaving the three Martyn ladies to fend for themselves on a reasonable but limited inheritance. I know Dorothea only from a worn black and white published photograph. To my eye she was the more beautiful of the two daughters but she died at a young age from an eating disorder and her elder sister, once voted by her peers as “the most beautiful girl in the mid-west”, moved to London where she married the Irish portrait painter, John Lavery in 1909.

Hazel Lavery got it into her head in mid-1916 that she would try to reconcile Ireland and England who had been more or less in serious disagreement for seven hundred years since the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1169. She asked John to paint the portraits of the leading Anglo Irish figures and while they were sitting for their portraits at the family home and studio on 5 Cromwell Place in London, she helped coax them around to a shared view which they signed in December 1921 in the form of the Anglo Irish Treaty granting independence to the southern part of Ireland. They say the rest is history; don’t they?

It is a long way from a pig sty in Milwaukee to 10 Downing Street in London. Many paths have divided and sub-divided in the woods. To join the dots of history in this manner is in many ways complete nonsense; to infer that it was the relationship between the pig and mankind which had unlocked one of the most intractable disputes of all time, is a ludicrous if convenient for now misrepresentation. Edward Jenner Martyn would likely have succeeded in any number of professions and his biological clock would probably have stopped his heart around the same time no matter where he worked or lived. Leaving aside the infinitely fantastic game of chance that the same conception of his two beautiful daughters would have occurred regardless also of his profession or place of residence, one might still, even if unreasonably, ask the question as to whether Hazel would have found her way to London as she did in 1909 were it not for the pigs of Milwaukee.

And these “what if” theories of history can be such a fruitless enterprise. Wordsworth reminds us that the past has delivered us our present whether we like it or not. But what if we were to take out the slightest piece of the past; remove a moment’s whim? The present might be completely different. This makes the tiniest and most private moment as important as the great events of world history; important in the sense that they have meaningful impact — maybe even more important than the Waterloos and Alamos in relative terms because of their power-to-weight ratios.

So that’s what I will say from now on if anyone asks me how the Irish finally won their independence. I will start by telling them about the mid-nineteenth century pigs at the Armour Meat Packing Company in Milwaukee. Any excuse to talk about the Laverys.

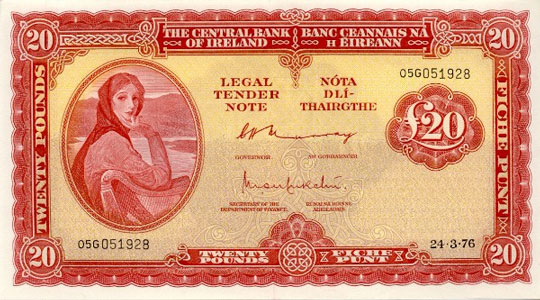

When it came to designing the currency for the new independent Ireland in 1927 a portrait of Hazel Lavery representing Irish female beauty was adopted for all of the paper currency. The Currency Commission under the chairmanship of poet W.B. Yeats picked a series of farm animals for the coins. I like to think now that it was a Milwaukee pig that made the humble Irish halfpenny.

It is Hazel Lavery’s birthday on St Patrick’s day. She will be one hundred and twenty five this year [2005]. I will go as I do most years on 17th March to the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art in Dublin to see her. It will be closed as it usually is on her birthday but I like to make the effort. It’s the least I can do…

Editor’s Note:

Hazel, Lady Lavery (1880-1935) was the wife of the painter Sir John Lavery. Hazel Lavery’s face became well known to Irish people because it was her engraved portrait which graced the Irish pound note until 2002.

During the negotiations for the Anglo-Irish Treaty in London in 1921, Sir John, and especially Lady Lavery, facilitated meetings between Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith of the Irish Delegation and Winston Churchill, Lord Londonderry and other key members of the British delegation.

Hazel managed this through the circumstances of Sir John painting the portraits of all the leading Anglo Irish Delegation members and through several private meetings and dinners she arranged at the Lavery’s house at Cromwell Place in South Kensington and attended by those same key members of both delegations. It is generally regarded that that without Hazel there would have been no treaty; and certainly not at that time. It was the acceptance of the terms of that Treaty by Collins and the delegation that led to the subsequent Civil War in Ireland.

The Irish Free State government, which emerged from that war, invited Sir John Lavery, as a token of their appreciation for his help, to paint a portrait of his wife to be used on the Irish pound notes. Lavery painted Hazel dressed as a colleen and representing Irish female beauty and the legendary heroine Cathleen ni Houlihan. Hazel remained on the on the Irish pound note well into the 1970’s, and remained as the watermark until 2002, when the Republic joined the European Single Currency.

- You can find more of Hay Machine (e)’s poetic works at The Web Poetry Corner, including the full text of “Sir John and Lady Hazel Lavery” that was quoted at the start of this article.

- For more information on Hazel Lavery try: Hazel: a life of Lady Lavery, 1880-1935. This biography of Hazel Lavery by Sinead McCoole (Lilliput Press, 1996) reconstructs the life of this restless, pioneering society beauty and sheds light on some of Ireland`s most revered patriots and the early history of the state.

This article “Hazel Lavery, Milwaukee Pigs and the Fight for Irish Freedom” © Hay Machine (e) and written especially for Porkopolis.org. The poem “Sir John and Lady Hazel Lavery” © Hay Machine (e). They are both used with permission of the author, as facilitated by our good friend Terence Brown.